To an untrained eye, the aircraft engine sitting outside of a Cincinnati facility in December might have looked like standard hardware. But NASA and GE Aerospace researchers watching the unit fire up for a demonstration knew what they were looking at: a hybrid engine performing at a level that could potentially power an airliner.

It’s something new in the aviation world, and the result of years of research and development.

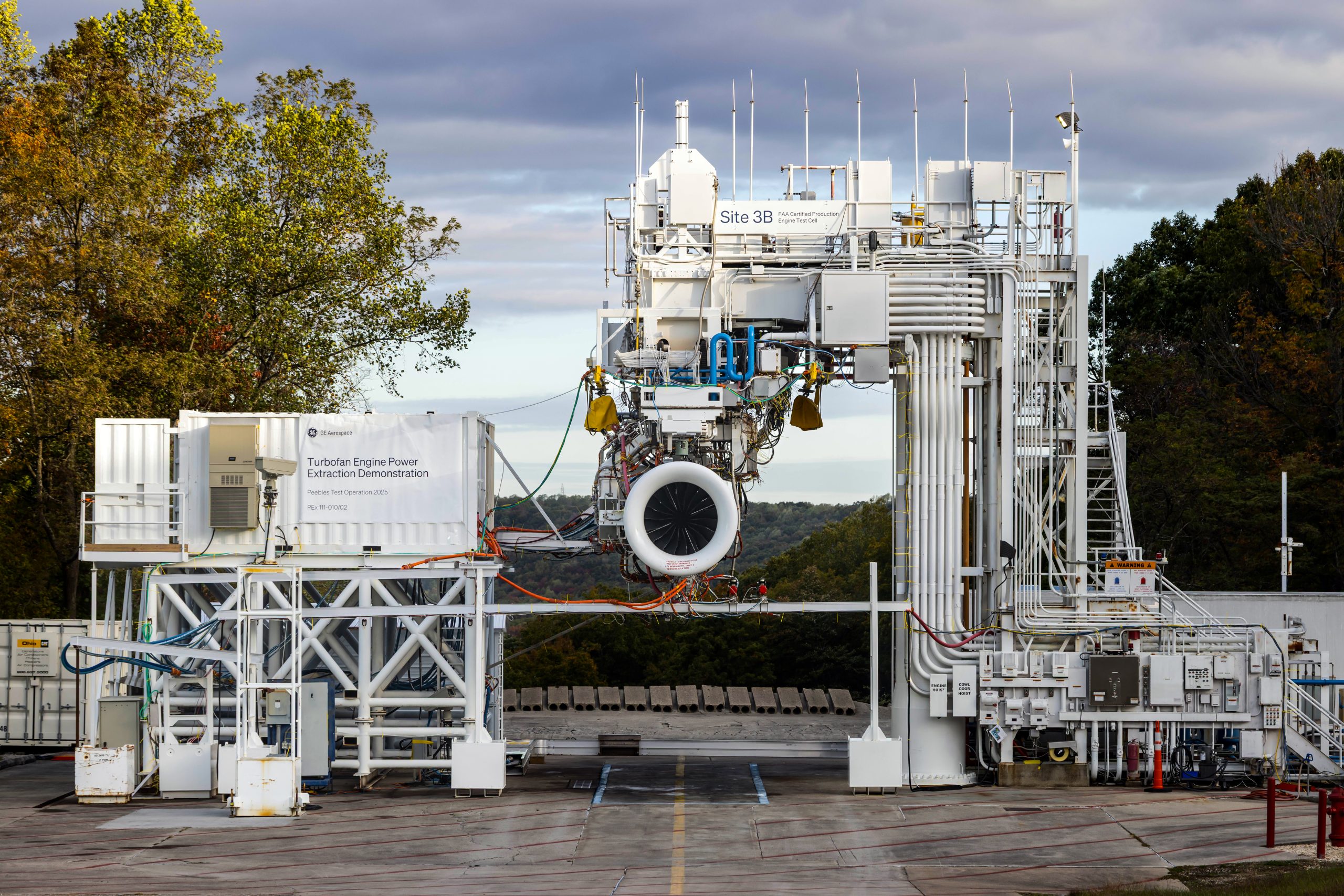

NASA, GE Aerospace, and others working toward hybrid engine development had already tested components in the past — power system controls, electric motors, and more. What the demonstration at GE Aerospace’s Peebles Test Operation site in Ohio represented was the first test of an integrated system.

“Turbines already exist. Compressors already exist. But there is no hybrid-electric engine flying today. And that’s what we were able to see,” said Anthony Nerone, who served as manager of the agency’s Hybrid Thermally Efficient Core (HyTEC) project at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland during the test engine’s development.

The test involved a modified GE Aerospace’s Passport engine with the ability to extract energy from some of its operations and insert that supplementary power into other parts.

The hybrid engine is result of research from GE Aerospace and NASA under a cost-sharing HyTEC contract. It runs on jet fuel with assistance from electric motors, a concept that seems simple in a world where hybrid cars are common. Yet the execution was complex, requiring researchers to invent, adapt, and integrate parts into a system that could deliver the requisite power needed for a single-aisle aircraft safely and reliably.

As a result, the demonstration — known as a power extraction test — was one of the most complex GE Aerospace has staged to date.

“They had to integrate equipment they’ve never needed for previous tests like this,” said Laura Evans, acting HyTEC project manager at Glenn.

Despite the complexity, the team witnessed a successful demonstration. Not a balancing test or a preliminary exercise, but an engine on a mount doing many of the things it would need to do if installed in an aircraft.

The test comes at a time when U.S. aviation is increasingly looking for power systems that can do more while also saving money on fuel. It’s a trend NASA was well ahead of. Hybrid aircraft engine technology began to emerge from Glenn roughly 20 years ago, when it seemed nearly impossible to realize, Nerone said.

“Now,” he said. “When you go to a conference, hybrid technology is everywhere.”

And NASA and GE now have real data for how the technology can be applied to flight.

From that early start, NASA transitioned into HyTEC and its contract with GE Aerospace.

HyTEC’s goal is to mature technology that will enable a hybrid engine that burns up to 10% less fuel compared to today’s best-in-class engines. NASA’s overall goal is to leverage its resources to bring the technology to market faster, meeting industry needs.

The work is far from over. Both NASA and GE Aerospace are analyzing data from the demonstration and from previous work and are making progress toward a compact engine test this decade.

Still, the demonstration was a chance to see the integration of technology that’s closer than ever to practical application.

“We’re getting close to the payoff on work that’d been in progress for a long time,” Nerone said.